Monday, 8:20 AM - Energy is coursing through my veins. My hands are clammy. All of my senses are heightened. My thoughts are racing, and I’m starting to panic. I know that I waited until the last minute to study for this exam, but this visceral, overdramatic response seems far too excessive for what I am facing.

Thursday 6:15 AM - I wake up. Another dreary day. I lay there glued to the bed. Gravity seems to be working 10 times as hard on me today. I can practically feel myself sinking into the bed. I feel a massive amount of energy buzzing around me. But instead of compelling me into action, it feels like it's actively trying to hold me down. I feel trapped. Paralyzed. So uncertain, so overwhelmed that not moving seems like the only option available to me.

Background: Struggling with Stress

This is how anxiety and depression manifests in me. And for so long I thought something was wrong with me. But what if I told you that these fight, flight, or freeze responses were natural reactions? What if I told you that this is my brain’s attempt to take care of me? That it—my brain—is actually practicing compassion towards me, but these survival mechanisms are maladapted for today’s cultural environment. What if I told you that we all share this struggle? And that our relationship with this stress has huge implications on our health and longevity?

Why This is Important

A research study tracked 30,000 adults in the United States for eight years. And they started by asking people, “how much stress have you experienced in the last year?” They also asked, “Do you believe that stress is harmful for your health?” And then they used public death records to find out who died.

People who experienced a lot of stress in the previous year had a 43% increased risk of dying. But that was only true for the people who also believed that stress is harmful for your health. People who experienced a lot of stress but did not view stress as harmful were no more likely to die. In fact, they had the lowest risk of dying of anyone in the study, including people who had relatively little stress.1

People don't have to suffer as much as they do. Trauma (and previous conditioning) makes the past overdetermine the present and conjures up a future that identifies with doom and chaos. BUT, you change your perspective about these past experiences by changing your interpretive frameworks.

For most of my life I had been shackled by these overwhelming feelings, so coming to this realization earlier this year was a crucible moment2 for me. I feel like this changed perspective upgraded my operating system, and unlocked this high-performance mode within me that I never knew existed. Just think: when our ancestors were still hunter-gatherers, this “stress” could actually have been considered “vigilance” because (at the time) it was a useful instinct that improved their chances of survival.

Armed with this new awareness, my hope is that you can begin to:

Stop shaming yourself

Start healing

Start using this newfound energy to propel yourself

Problem: The Software Got Upgraded, The Hardware Did Not

In our advanced civilized society, we have become so disconnected from what it means to feel human. We mistake negative emotions, like stress, and its cousins—procrastination, anxiety and depression—as weakness of character. In reality, these are beacons, signals that something isn't right. If we can reframe how we look at these stressors, we can change our brain and our body's response to them.

Constantly Feeling Like a Deer in the Headlights

When a deer sees an incoming car, it freezes [instinctively]. For us, it looks stupid. [But to the deer, freezing] would be the best reaction if the car were a predator: too big to fight, too fast to outrun. By freezing it hopes that the beast fails to spot it, or gets distracted.3

The panic right before an exam, or the pulsating paralysis of waking up and thinking of all the things I’m behind on, all the things I haven’t done yet—my body instinctively thought these were the right reactions. Just like the deer in the headlights. And for so long I couldn’t figure out the point of these reflexes. As I dug deeper into our human biology, I began to realize that these were manifestations of energy (albeit negative)—remnants of a time long ago when humans did not rule the planet.

The human brain did not evolve to live in a delayed-return environment. It spent hundreds of thousands of years evolving in an immediate-return environment. Within the last 500 years it all changed.4 The new delayed-return environment has led to chronic stress and anxiety for humans, because those emotions are no longer useful to help us take action in the face of immediate problems.

We essentially have an ancient alarm system that is often triggered by things that aren't true threats to us. Paradoxically, the way to fix that hairpin trigger is tuning in—with loving awareness—and letting ourselves fully feel all of the fight, flight, or freeze trauma that our body is carrying with us at that moment. And once we’ve done that, we can thank our brains for trying to protect and keep us safe.5

Solution: What to Do About It

How to Recognize & Respond (With Compassion)

Step 1 - Recognize: Where you're at emotionally

Whenever you become distressed—try to check if it feels like a fight, flight, or freeze response. Focus on the sensation; observing and experiencing, but not judging.

Below are some emotions and their corresponding fear responses6

FIGHT: anger / pushing

FLIGHT: distracting oneself

FREEZE: numbness, depression, learned helplessness

After you’ve become aware of being triggered, determine how intense the emotions are because that will inform what strategy to use. To do this, check in with your body:

Are your fists clenched?

Are your teeth clenched?

Is your stomach tight?

Are you fighting back tears?

Is your face feeling flushed?

Step 2 - Respond: with a strategy that makes sense for your level of emotional intensity

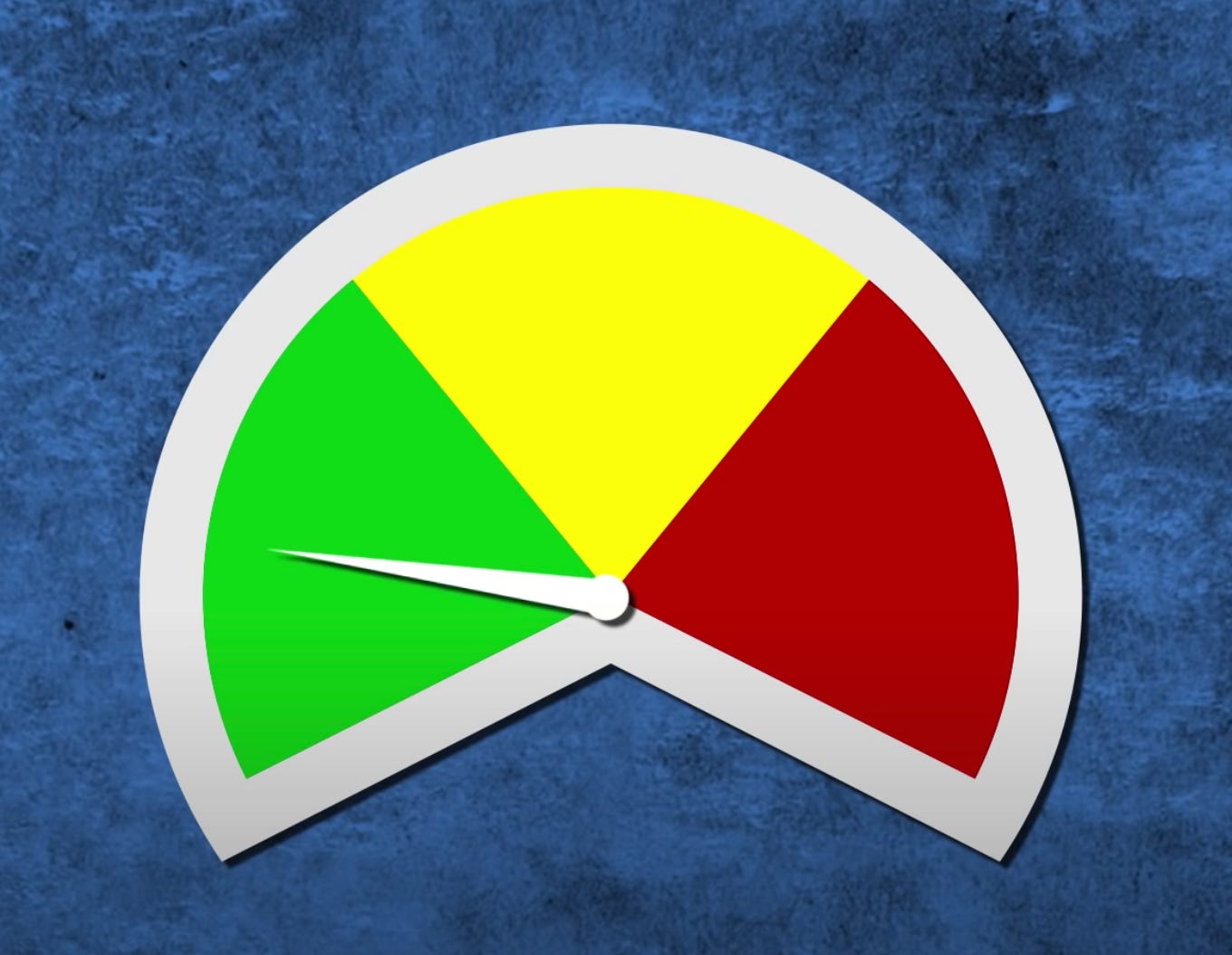

Red: our emotions are so high that we're entering fight, flight, or freeze mode

This is the time to use time-tested strategies to help us feel safe, (I recommend box breathing7 as a way to return breathing to its normal rhythm)

This is not the time to engage others or make any brash decisions

Yellow: emotions are heightened, but we're somewhat in control

This is the time to use strategies to slow us down and calm our brains (like focusing on breathing, going on a short walk, drinking some tea)

Green: emotional intensity is normal, we're thinking clearly

This is the time when we feel our safest and most rational—a good time to work on issues that previously couldn't be handled because emotions were too high

Step 3 - Practice: Telling your body that you are not in danger

When you are “in the green” (emotionally), that’s a great opportunity to practice some exposure therapy—to practice telling your body that it’s not in danger. Exhausted muscles after intensive exercise, burning sensation from chili peppers, the heat of a sauna—these are all great examples of stimuli that you can use to help retrain your reactions to stress.

These self-awareness skills are not innate—they are like a muscle and need to be strengthened with exercise. When we practice telling our body that it’s not in danger, we are leaning into the discomfort and reducing its power. At the same time, it’s important to be patient with, and forgiving of, yourself as you go through these motions.

Treat your broken parts like a wounded puppy. Give them time to recover, and don’t push them to walk before they are ready. Don’t you deserve to treat yourself with the same level of compassion as you would this hypothetical puppy?

Carrying This Awareness Forward

Culturally, when we look at people with depression or anxiety, we often label their suffering as irrational and unnecessary, stigmatizing them and robbing them of hope.

But when we begin to understand that these manifestations of negative energy are adaptive responses to adversity and not mental disorders, we begin to lift the shame around them. And when that shame begins to lift, people who struggle with these emotions can start feeling like courageous survivors, and not damaged invalids.8

We often have this illusion that we’re the only one’s feeling whatever we're currently feeling, but we can reframe this by asking ourselves, "would anyone else in this situation feel the same thing?" When we reflect, we realize that what we’re going through is what all human beings go through. We are not crazy or specially defective in any way.

I believe that by cultivating self-awareness and self-compassion we can channel our negative emotions into life energy and be able to harness them to our advantage. Because the right amount of stress is called stimulation.

How to Make Stress Your Friend, Kelly McGonigal

A crucible moment is a transformative experience through which an individual comes to a new or an altered sense of identity

Don't fight, flight (or freeze) your body and emotions, by Piotr Migdał

The Evolution of Anxiety, by James Clear

The Fake News of Your Own Mind, Your Undivided Attention (Podcast)

Don't fight, flight (or freeze) your body and emotions, by Piotr Migdał

Box breathing is a technique used to calm yourself down with a simple 4 second rotation of breathing in, holding your breath, breathing out, holding your breath, and repeating.